Age, Biography and Wiki

Isaac Woodard was born on 18 March, 1919 in Fairfield County, South Carolina, U.S.. Discover Isaac Woodard’s Biography, Age, Height, Physical Stats, Dating/Affairs, Family and career updates. Learn How rich is He in this year and how He spends money? Also learn how He earned most of networth at the age of 73 years old?

| Popular As |

N/A |

| Occupation |

N/A |

| Age |

73 years old |

| Zodiac Sign |

Pisces |

| Born |

18 March 1919 |

| Birthday |

18 March |

| Birthplace |

Fairfield County, South Carolina, U.S. |

| Date of death |

(1992-09-23) |

| Died Place |

N/A |

| Nationality |

South Carolina |

We recommend you to check the complete list of Famous People born on 18 March.

He is a member of famous with the age 73 years old group.

Isaac Woodard Height, Weight & Measurements

At 73 years old, Isaac Woodard height not available right now. We will update Isaac Woodard’s Height, weight, Body Measurements, Eye Color, Hair Color, Shoe & Dress size soon as possible.

| Physical Status |

| Height |

Not Available |

| Weight |

Not Available |

| Body Measurements |

Not Available |

| Eye Color |

Not Available |

| Hair Color |

Not Available |

Dating & Relationship status

He is currently single. He is not dating anyone. We don’t have much information about He’s past relationship and any previous engaged. According to our Database, He has no children.

| Family |

| Parents |

Not Available |

| Wife |

Not Available |

| Sibling |

Not Available |

| Children |

Not Available |

Isaac Woodard Net Worth

His net worth has been growing significantly in 2022-2023. So, how much is Isaac Woodard worth at the age of 73 years old? Isaac Woodard’s income source is mostly from being a successful . He is from South Carolina. We have estimated

Isaac Woodard’s net worth

, money, salary, income, and assets.

| Net Worth in 2023 |

$1 Million – $5 Million |

| Salary in 2023 |

Under Review |

| Net Worth in 2022 |

Pending |

| Salary in 2022 |

Under Review |

| House |

Not Available |

| Cars |

Not Available |

| Source of Income |

|

Isaac Woodard Social Network

| Instagram |

|

| Linkedin |

|

| Twitter |

|

| Facebook |

|

| Wikipedia |

|

| Imdb |

|

Timeline

In January 2019, a new book about the Woodard story and its aftermath, Unexampled Courage: The Blinding of Sgt. Isaac Woodard and the Awakening of President Harry S. Truman and Judge J. Waties Waring, was published; it was written by Federal Judge Richard Gergel.

A group of veterans which was led by Don North, a retired Army major from Carrollton, Georgia, received permission to erect a historical marker in honor of Woodard in Batesburg-Leesville in South Carolina. In 2019 the marker was unveiled. The bottom part of the marker was written in Braille.

Woodard’s “drunk and disorderly” conviction was vacated in 2018.

Newspaper accounts vary on what happened next (and accounts sometimes spelled his name as “Woodward”), but author and attorney Michael R. Gardner said in 2003:

On November 5, after 30 minutes of deliberation (15, according to at least one news report), the jury found Shull not guilty on all charges, despite his admission that he had blinded Woodard. The courtroom broke into applause upon hearing the verdict. The failure to convict Shull was perceived as a political failure by the Truman administration. Shull was never punished, dying in Batesburg on December 27, 1997, at the age of 95.

Woodard moved north after the trial during the Second Great Migration and lived in the New York City area for the rest of his life. He died aged 73 in the Veterans Administration hospital in the Bronx on September 23, 1992. He was buried with military honors at the Calverton National Cemetery (Section 15, Site 2180) in Calverton, New York.

Welles revisited the Woodard case in the May 7, 1955, broadcast of his BBC TV series, Orson Welles’ Sketch Book. Woody Guthrie later recalled: “I sung ‘The Blinding of Isaac Woodard’ in the Lewisohn Stadium (in New York City) one night for more than 36,000 people, and I got the loudest applause I’ve ever got in my whole life.”

Such miscarriages of justice by state governments influenced a move towards civil rights initiatives at the federal level. Truman subsequently established a national interracial commission, made a historic speech to the NAACP and the nation in June 1947 in which he described civil rights as a moral priority, submitted a civil rights bill to Congress in February 1948, and issued Executive Orders 9980 and 9981 on June 26, 1948, desegregating the armed forces and the federal government.

On February 2, 1948, Truman sent the first comprehensive civil rights bill to Congress. It incorporated many of the thirty-five recommendations of his commission. In July 1948, over the objection of senior military officers, Truman issued Executive Order 9981, banning racial discrimination in the U.S. Armed Forces, and Executive Order 9980 to integrate the federal government. (Facilities had been segregated under President Woodrow Wilson). This was in response to a number of incidents against black veterans, most notably the Woodard case. The armed forces and federal agencies led the way in the United States for integration of the workplace, public facilities, and schools. Over the decades, the decision meant that both institutions benefited from the contributions of minorities.

Nevertheless, polls showed opposition to Truman’s civil rights efforts. They likely cost him some support in his 1948 reelection bid against Thomas Dewey. Although Truman narrowly won, Gardner believes that his continued championing of civil rights as a federal priority cost him much support, especially in the Solid South. Southern Democrats had long exercised outsize political power in Congress, having disfranchised most blacks there since the turn of the 20th century, but benefiting by apportionment based on total population. Truman’s efforts threatened other changes since numerous communities across the country had restrictive covenants that were racially discriminatory. Because of his low approval ratings and because of a bad showing in early primaries, Truman chose not to seek re-election in 1952, though he could have done so. He had been exempted from the term limitations which are imposed by the 22nd amendment.

Truman made a strong speech on civil rights on June 29, 1947, to the NAACP, the first American president to speak to their meeting, which was broadcast by radio from where they met on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. The President said that civil rights were a moral priority, and it was his priority for the federal government. He had seen by Woodard’s and other cases that the issue could not be left to state and local governments. He said:

On February 12, 1946, Woodard was on a Greyhound Lines bus traveling from Camp Gordon in Augusta, Georgia, where he had been discharged, en route to rejoin his family in North Carolina. When the bus reached a rest stop just outside Augusta, Woodard asked the bus driver if there was time for him to use a restroom. The driver grudgingly acceded to the request after an argument. Woodard returned to his seat from the rest stop without incident, and the bus departed.

On his ABC radio show Orson Welles Commentaries, actor and filmmaker Orson Welles crusaded for the punishment of Shull and his accomplices. On the broadcast which was made on July 28, 1946, Welles read an affidavit which was sent to him by the NAACP and signed by Woodard. He criticized the lack of action by the South Carolina government as intolerable and shameful. Woodard was the focus of Welles’s four subsequent broadcasts. “The NAACP felt that these broadcasts did more than anything else to prompt the Justice Department to act on the case,” wrote the Museum of Broadcasting in a 1988 exhibit on Welles.

On September 19, 1946, seven months after the incident, NAACP Executive Secretary Walter Francis White met with President Harry S. Truman in the Oval Office to discuss the Woodard case. Gardner writes that when Truman “heard this story in the context of the state authorities of South Carolina doing nothing for seven months, he exploded.” The following day, Truman wrote a letter to Attorney General Tom C. Clark demanding that action be taken to address South Carolina’s reluctance to try the case. Six days later, on September 26, Truman directed the Justice Department to open an investigation.

In December 1946, after meeting with White and other leaders of the NAACP, and a month after the jury acquitted Shull, Truman established the Civil Rights Commission by Executive Order 9808; a fifteen-member, interracial group, including the President of General Electric, Charles E. Wilson; academics such as John Sloan Dickey from Dartmouth College; and Sadie Tanner Alexander, a black attorney for the city of Philadelphia, as well as other activists. He asked them to report by the end of 1947.

On October 14, 1942, the 23-year-old Woodard enlisted in the United States Army at Fort Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina. He served in the Pacific theater in a labor battalion as a longshoreman and was promoted to sergeant. He earned a battle star for his Asiatic–Pacific Campaign Medal by unloading ships under enemy fire in New Guinea, and received the Good Conduct Medal as well as the Service medal and World War II Victory Medal awarded to all American participants. He received an honorable discharge.

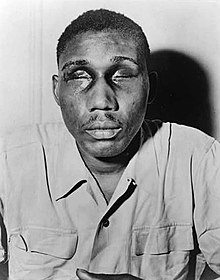

Isaac Woodard Jr. (March 18, 1919 – September 23, 1992) was an American soldier and victim of racial violence. An African-American World War II veteran, on February 12, 1946, hours after being honorably discharged from the United States Army, he was attacked while still in uniform by South Carolina police as he was taking a bus home. The attack and his injuries sparked national outrage and galvanized the civil rights movement in the United States.