China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi will visit Cambodia this weekend as part of his three-country tour to Southeast Asia that also includes Singapore and Malaysia. This is Wang’s first visit abroad after replacing his successor Qin Gang as foreign minister in late July, following Qin’s short-lived tenure and mysterious disappearance from the public eye.

Wang will arrive in Phnom Penh in the midst of a high-stake transition, in which long-time Prime Minister Hun Sen is stepping down after more than 38 years in power, to be replaced by his eldest son, Hun Manet, who is scheduled to take office on August 22. It’s not only him; almost all of the old-guard cabinet members will leave their posts to make ways for younger officials, in some cases the children of the current ministers. Wang’s visit will be significant for both the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP)’s quest for international legitimacy and the future of Sino-Cambodian relations during an era of new leadership in Phnom Penh.

Wang has often visited Cambodia at important political junctures. Not long after first becoming foreign minister in 2013, Wang visited Phnom Penh shortly after the CPP had suffered a shocking drop in popularity to the then-rising Cambodia National Rescue Party, which its domestic and international standing was severely under threat. At the time, Wang declared that Beijing would defend Phnom Penh against foreign interference during its political crisis. Similarly, in 2018, after the CPP collected all 125 parliamentary seats as a result of the one-horse race election that year, Wang met his Cambodian counterpart Prak Sokhonn in Singapore and promised that China would shield the Cambodian government from Western pressure.

His weekend debut in Phnom Penh will lay the groundwork for a new chapter of bilateral relations with the new political leadership in Cambodia. During his planned meetings with Hun Manet and incoming Foreign Minister Sok Chenda Sophea, Wang will use the opportunity to woo new Cambodian cabinet ministers to ensure the preservation of the status quo in bilateral relations, which the most recent official discourse refers to as a “diamond hexagon.”

Diplomat Brief

Weekly Newsletter

Get briefed on the story of the week, and developing stories to watch across the Asia-Pacific.

Get the Newsletter

Beijing is naturally concerned that the new faces of the Cambodian government may hedge and offer itself to reset relations with the West at the expense of China’s existing influence. Wang’s visit will aim to receive assurance that Chinese interests will be well-protected by the new Cambodian leaders, most of whom, including Hun Manet, studied and spent many years in the West.

To be sure, under Manet’s leadership, the Cambodian army held the Dragon Gold military exercise with China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) three times (in 2019, 2020, and 2023). It also signed a memorandum of understanding with the PLA Ground Force last year. Despite paying visits to India, Russia, Singapore, Japan, and all three neighboring states (Thailand, Vietnam, and Laos) since his appointment as army commander in 2018, Manet has not visited China in this capacity.

However, Hun Manet has twice visited Beijing as part of his father’s entourage. He accompanied Hun Sen to Beijing in February 2020 at the height of the first COVID-19 outbreak in China, and again in February of this year, shortly after China reopened the country from its “zero COVID” strategy. On the latter occasion, he met separately with Gen. Zhang Yuxia, the second-in-command of the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Military Commission, after which two different readouts were released. China’s readout of the meeting cited Manet as saying that Cambodia “stands firm in upholding the one-China policy and is willing to advance the joint building of Belt and Road with China.” Similar contents were nowhere to be seen in Cambodia’s readout, which stressed that “both sides agreed on maintaining the status quo of a peaceful, stable, and developed Asia Pacific enjoyed by countries and people in the region and resolving any challenges on the ground of rules-based international order.”

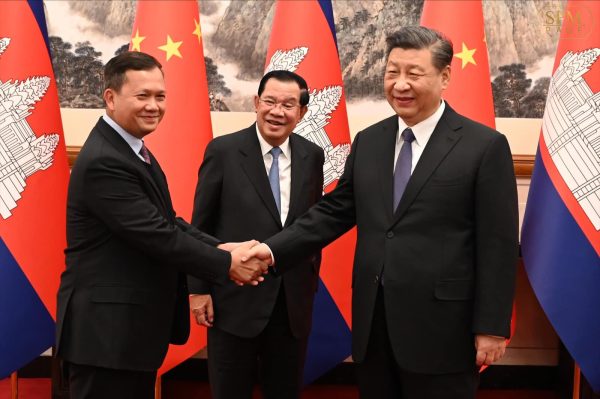

Wang Yi met both Hun Sen and Hun Manet during the ASEAN meetings that were held in Phnom Penh in August of last year. Cambodian state media were quick to report that “China threw support behind the next Cambodian leader and praised Hun Manet as mature with a far-sighted vision like his father.” The Chinese statement was more reserved. It stated that China would “work with Cambodia to deepen strategic communication and carry forward the traditional friendship, so that the friendship between China and Cambodia will be passed on from generation to generation with enduring vitality.”

Advertisement

Despite these differing points of emphasis, Cambodia-China relations are unlikely to take a huge hit amid the leadership changes in Phnom Penh.

With Hun Sen set to remain politically active within the CPP while a number of his elderly colleagues will oversee the young cabinet from their perches on the CPP Politburo, China still has good contacts with and access to the party’s leadership. Moreover, the party’s and the country’s interests will remain closely embedded with China, despite the young cabinet’s strong Western profiles.

Politically, Chinese political support will also remain crucial for the new CPP cabinet if it is to resist Western pressure and maintain the party’s near-absolute political monopoly.

Economically, China holds a third of Cambodia’s national debt. Chinese state-owned enterprises are investing, building, and operating key and critical infrastructures essential to Cambodian economy, including airports in Phnom Penh, Siem Reap, and Koh Kong, high-speed rail projects, and a man-made shipping canal connecting Phnom Penh and the Gulf of Thailand. Without cohesive and attractive alternatives from Western governments, Chinese intervention in upgrading Cambodian infrastructure will continue to be important for the CPP, which will hope to prove to Cambodian voters that the party will provide them with better roads, more bridges, world-class airports, and more economic connectivity and prosperity.

Militarily, China will remain the chief patron for the Cambodian armed forces, granting the latter much-needed access to new defense technologies, military hardware, and training. This is evident at the Ream Naval Base, which will significantly augment the capacity of the Cambodian navy. Whether China will have access to the base in the future depends on how the new Cambodian leadership will approach the China question, and whether they have the audacity to strike out in pursuit of a genuinely multipolar foreign policy.

Given that relations with China will remain close, much depends on whether both Cambodia and Western governments can work together to find compromises on the issues that have bedeviled bilateral ties, chief among them the CPP’s subversion of the country’s democratic system over the past decade. It is important to note that introducing radical democratic reforms would likely undermine the CPP’s dominance, suggesting that there are limits to how far the new government can go in assuaging Western concerns on this front. Striking a balance between a limited democratic opening and the CPP’s continued dominance will determine whether the CPP government can improve its relations with the United States and the European Union.”

The future trajectory of Cambodia-China relations will also depend to some extent on the CPP’s factional politics and China’s capability to engage different interest groups inside Cambodia’s ruling party.

However, Cambodia’s new guard leadership, led by Hun Manet, have expressed their wish to maintain the country’s neutrality within a “rules-based independent foreign policy” by engaging other nations, in order to escape the binary dilemma of having to choose between China or the United States. Manet said in a speech last year that the Cambodia he will rule won’t pick sides. The new generation therefore deserves time, space, and attractive alternatives from other partners in order to navigate through this shaky geopolitical context. Cambodia’s future neutrality rests on how the young guard strikes a balance between the U.S. and China, between multiparty democracy and political monopoly, and between national and party interests.