Age, Biography and Wiki

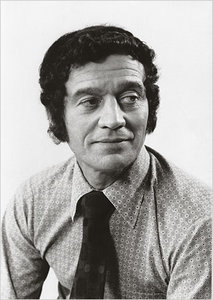

Anatole Broyard was born on 16 July, 1920 in New Orleans, Louisiana, US, is a writer. Discover Anatole Broyard’s Biography, Age, Height, Physical Stats, Dating/Affairs, Family and career updates. Learn How rich is He in this year and how He spends money? Also learn how He earned most of networth at the age of 70 years old?

| Popular As | N/A |

| Occupation | N/A |

| Age | 70 years old |

| Zodiac Sign | Cancer |

| Born | 16 July 1920 |

| Birthday | 16 July |

| Birthplace | New Orleans, Louisiana, US |

| Date of death | (1990-10-11) |

| Died Place | N/A |

| Nationality | Louisiana |

We recommend you to check the complete list of Famous People born on 16 July.

He is a member of famous writer with the age 70 years old group.

Anatole Broyard Height, Weight & Measurements

At 70 years old, Anatole Broyard height not available right now. We will update Anatole Broyard’s Height, weight, Body Measurements, Eye Color, Hair Color, Shoe & Dress size soon as possible.

| Physical Status | |

|---|---|

| Height | Not Available |

| Weight | Not Available |

| Body Measurements | Not Available |

| Eye Color | Not Available |

| Hair Color | Not Available |

Who Is Anatole Broyard’s Wife?

His wife is Aida Sanchez (divorced) – Alexandra (Sandy) Nelson

| Family | |

|---|---|

| Parents | Not Available |

| Wife | Aida Sanchez (divorced) – Alexandra (Sandy) Nelson |

| Sibling | Not Available |

| Children | 3 |

Anatole Broyard Net Worth

His net worth has been growing significantly in 2022-2023. So, how much is Anatole Broyard worth at the age of 70 years old? Anatole Broyard’s income source is mostly from being a successful writer. He is from Louisiana. We have estimated

Anatole Broyard’s net worth

, money, salary, income, and assets.

| Net Worth in 2023 | $1 Million – $5 Million |

| Salary in 2023 | Under Review |

| Net Worth in 2022 | Pending |

| Salary in 2022 | Under Review |

| House | Not Available |

| Cars | Not Available |

| Source of Income | writer |

Anatole Broyard Social Network

| Wikipedia | |

| Imdb |