In 2023, North Korea actively navigated the international geopolitical landscape, fortifying its security coalitions with China and Russia amid China-U.S. tensions and the protracted Russia-Ukraine war. Pyongyang also advanced its nuclear capabilities according to the timeline set during the 8th Party Congress in 2021. This included the successful testing of solid-fuel engines for the Hwasong-18 intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) after two initial failures and the deployment of a military reconnaissance satellite, Manrikyeong-1, also after two failed attempts. The introduction of the new submarine Hero Kim Gun-ok, equipped with submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBM), added to North Korea’s ongoing nuclear capability development.

The already heightened tension on the Korean Peninsula in 2023 is expected to rise much higher in 2024. From the beginning of the new year, Kim Jong Un ordered North Korea’s military force, munitions industry, and nuclear weapons sector to accelerate war preparations to counter what he defines as “the enemies’ reckless moves for invading the DPRK,” a reference to North Korea’s formal name, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

In 2023, the South Korea-U.S. alliance took a significant stride towards bolstering its deterrent posture against North Korean threats. The 70th anniversary of the alliance witnessed a steadfast commitment to the historic Washington Declaration and the formation of the bilateral Nuclear Consultative Group (NCG). The alliance also enhanced the regular visibility of U.S. strategic asset deployments to the peninsula, through the visit of a nuclear-capable submarine, the USS Kentucky, and the landing of a B-52H strategic bomber on South Korean territory.

Despite these efforts, a notable gap or divergence persists among decision-makers between and even within both countries concerning how to assess North Korean threats and how to respond to them. This article seeks to delve into five key debates that hinder the achievement of an allied integrated approach in dealing with these grave threats. By fostering a shared perspective and stronger alliance cohesion, the South Korea-U.S. alliance can pave the way for the further development of the alliance’s deterrence posture.

The Five Key Debates

In evaluating the North Korean nuclear threat, the central question revolves around the end state that Pyongyang aims to achieve through the expansion of its nuclear weapons arsenal. On one end of the spectrum, some argue that North Korea’s goal is to maintain the status quo, prioritizing the survival and security of the Kim regime. On the opposite end, there is a contention that Kim Jong Un intends to occupy the Republic of Korea by making use of nuclear weapons in the event of a war, as indicated by his speech at the 10th Session of the 14th Supreme People’s Assembly (SPA) in January 2024.

The purposes behind Pyongyang’s use of nuclear weapons are commonly classified into three distinct motives: coercive, offensive, or defensive. Each of these motives corresponds to different scenarios of nuclear use. Is Pyongyang most likely to: a) deploy nuclear weapons to target a military base to impede prompt reinforcement from the United States, b) launch an attack on Seoul and the metropolitan area to swiftly dominate the South, or c) utilize its nuclear weapons solely as a deterrent? Consensus on the likelihood of these scenarios is urgent, as it is reported that the participants of the second Nuclear Consultation Group agreed on a plan to incorporate scenarios of nuclear operations in 2024 allied military exercises.

Second, there are varying levels of concern regarding whether North Korea’s nuclear actions will align with simultaneous moves by China and/or Russia. While most American experts are worried about the possibility of opportunistic or collaborative concurrent aggression from two nuclear peers, only a few Korea watchers caution that the United States might find itself in a situation of having to contend with both China and North Korea simultaneously. Moreover, recent military cooperation between Russia and North Korea introduces the potential that Pyongyang and Moscow could conspire to execute a strategic move together against the U.S. and its allies in the region.

The future outlook for such combined aggression will depend on the extent to which coordination among North Korea, China, and Russia can evolve to encompass the military dimension, despite the historical mutual distrust among the three nations. However, close coordination with others may not be a prerequisite for North Korea to decide on an opportunistic move. For instance, in the event of a conflict between the United States and China over Taiwan, North Korea might exploit the diverted attention of the U.S. to attack the Korean Peninsula.

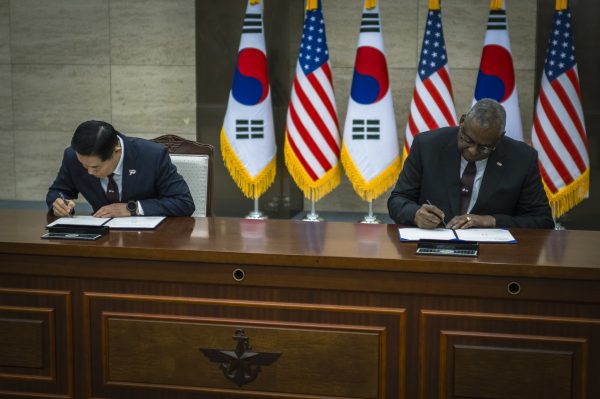

Third, the most sensitive debate between the two countries is about the specific U.S. military capabilities to be used in responding to a North Korean nuclear attack. At the last South Korea-U.S. Security Consultative Meeting held in November 2023, the U.S. defense secretary reiterated “the firm U.S. commitment to provide extended deterrence to the ROK, utilizing the full range of U.S. defense capabilities, including nuclear, conventional, missile defense, and advanced non-nuclear capabilities.” There is complete alignment in their objective in the event of any nuclear attack by Pyongyang, which is to bring about the end of the Kim regime with all available capabilities.

However, experts in the two countries tend to disagree on which capabilities would be most effective in deterring nuclear aggression. Many South Korean experts want the United States to make a declaration that it would use nuclear weapons in response to a North Korean nuclear attack because they believe such a U.S. statement could become the strongest deterrence message to Pyongyang. However, most U.S. experts argue that the U.S. government is not likely to make such a declaration, as nuclear use falls within the sole authority of the U.S. president. They add that any U.S. president will use nuclear weapons if absolutely necessary, but the U.S. has many (and, in some sense, even better) conventional options to achieve the shared objective. Threatening a nuclear response to the enemy might prompt unlimited escalation, not to mention its actual use.

Fourth, there are challenges in developing South Korea’s 3K Defense (Kill Chain, Korea Air and Missile Defense or KAMD, and Korean Massive Punishment and Retaliation or KMPR) system, also known as the Three-Axis System. The system comprises conventional capabilities, with each “K” element supporting a different operational concept, namely preemptive strikes, air and missile defense against a North Korean attack, and retaliatory strikes.

The 3K defense system had been developed for years before the 2023 Washington Declaration, which noted that the two countries would closely connect the capabilities and planning activities of the new Republic of Korea (ROK) Strategic Command and the existing U.S.-ROK Combined Forces Command. The ROK STRATCOM, set to be established in 2024, aims to enhance the country’s non-nuclear strategic deterrence through unified command and control over the 3K Defense system.

The South Korea-U.S. alliance has formulated the “Tailored Deterrence Strategy (TDS)” as a joint strategy since 2013. However, until the update in 2023 prompted by the Washington Declaration, there had been a lack of comprehensive efforts to align Seoul’s plan with U.S. strategic planning. One of the crucial points of contention revolves around the augmentation of retaliatory capabilities. The KMPR aims to respond to a nuclear attack by targeting the enemy’s war leadership, particularly in Pyongyang, and essential military facilities. Nevertheless, the difficulty lies in distinguishing non-combatants from combatants. There is a need to reconcile disparities in international treaties and rules of engagement (RoE) applied by both the U.S. and South Korea. Furthermore, the political debate surrounding the effectiveness of signaling leadership targeting, commonly referred to as “decapitation,” must be considered.

Lastly, should deterrence fail, the question of the extent to which costs from the South Korea-U.S. alliance can be tolerated is seldom addressed. Both the U.S. homeland and South Korean territory are potentially at risk of a nuclear first strike by North Korea. General Glen D. VanHerck, commander of U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM) and North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), has officially expressed concern about the U.S. capacity to defend itself against ICBM attacks from North Korea in the coming decade.

Moreover, Pyongyang is openly enhancing the survivability of its missiles by developing technologies such as solid fuel engines, hypersonic capabilities, and multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs). If Pyongyang is emboldened to attack with strategic impact, intercepting all missiles from North Korea heading toward the alliance and preventing damage is unlikely.

We want to believe that Kim Jong Un is a rational actor, but a potential erosion of the alliance’s credibility in denial capabilities may increase his incentive to launch an attack. The narrowest width of the Korean Peninsula is near the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), the border between the two Koreas, which is only 120 miles from coast to coast. Seoul and Pyongyang, the most populous capital cities of South and North Korea, are situated close to their respective borders. A highly intense armed conflict is anticipated around the zone should a war eventually occur.

Risk is shared with Americans. According to data from 2022, 582,000 Americans live in South Korea, with approximately 28,500 of them being U.S. Forces Korea. North Korea frequently threatens targets in the U.S. homeland as well, including military bases in Guam, Hawaiʻi, and Alaska.

Toward a More Integrated Approach

Past observations suggest that North Korea is unlikely to provoke hastily, preferring to await a favorable international environment to maximize its strategic options. North Korea has demonstrated the capacity for such perseverance, exhibiting political, economic, and social resilience even during the COVID-19 lockdowns. Until the opportune moment arrives, North Korea will strive to modernize its outdated conventional military capabilities and structures while ambitiously pursuing advancements in nuclear technology to enhance its preparedness for war against the South Korea-U.S. alliance. To showcase its military capabilities, North Korea may demonstrate enhanced nuclear capabilities from advantageous positions or actively engage in conventional provocations to reveal vulnerabilities in the ROK’s defense.

The current policy direction taken by the South Korea-U.S. alliance involves even stronger pressure on North Korea, increasing the visibility of the combined alliance. posture. However, differences in perspectives and approaches within the alliance impose invisible yet potent restraints on alliance cohesion, which is at the core of the allied deterrence posture.

While it is acknowledged that the alliance is already moving forward, with limited time for discussion, it is crucial to act before it becomes too late. In this year of formidable challenges, the South Korea-U.S. alliance should mark a significant step forward by adopting a consensus-based and well-structured approach through more intense and open discussions on North Korea’s nuclear strategy, more detailed contingency scenarios, and frank appraisals of the vulnerabilities of the alliance posture.