WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court on Thursday ruled that silkscreens pop artist Andy Warhol made of rock star Prince infringed on the copyright held by a prominent photographer who captured the original image.

In a win for photographer Lynn Goldsmith, the court ruled 7-2 that Warhol’s images did not constitute “fair use” under copyright law, a decision that will have considerable impact on various creative industries. The ruling is beneficial to people who own copyrighted content upon which other works are based, and could have a negative impact upon entities that make new works based on existing material.

Whether a work is used for a commercial purpose is just one of various factors used to analyze copyright infringement.

The court in a ruling authored by Justice Sonia Sotomayor concluded that the works made by Warhol did not have a sufficiently different commercial purpose from that of the original photo taken by Goldsmith: Both are used to illustrate magazine articles about Prince.

Sotomayor wrote that the images “share substantially the same purpose, and the use is of a commercial nature.” The Warhol foundation had “offered no other persuasive justification for its unauthorized use of the photograph,” she added.

Sotomayor said the ruling was a narrow one, noting that even other works by Warhol — including his famous images of Campbell’s soup cans — would be analyzed differently. While the Prince images were used to illustrate a magazine story, which is the same purpose for which Goldsmith’s photos would be used, the soup cans series “uses Campbell’s copyrighted work for an artistic commentary on consumerism,” Sotomayor wrote.

Justice Elena Kagan wrote a biting dissenting opinion, joined by Chief Justice John Roberts, criticizing fellow liberal Sotomayor.

She said the majority downplayed the impact of Warhol’s artistry in transforming the nature of the images by focusing instead on the fact that he had engaged in a commercial arrangement with a magazine.

“Because the artist had such a commercial purpose, all the creativity in the world could not save him,” she wrote. The ruling will cramp artists and creativity because any artwork that uses existing materials is in danger of violating copyright law, Kagan wrote.

As a result the ruling “hampers creative progress and undermines creative freedom,” she added.

Kagan dismissed Sotomayor’s attempt to distinguish the soup can images, saying the court was “slicing the baloney pretty thin.”

During the lively oral argument in October, in which conservative Justice Clarence Thomas admitted he was once a Prince fan, the justices invoked artists as diverse as Renaissance master Leonardo da Vinci and rap group 2 Live Crew.

The case raised a legal question of considerable interest to people in all kinds of creative industries, including television, film and fine art. It required the court to wrestle with how to define whether a new work based on an existing one is “transformative” — meaning it does not violate copyright law. Under the law, limited “fair use” of a pre-existing artwork is lawful in certain contexts, including when the new work conveys a different meaning or message.

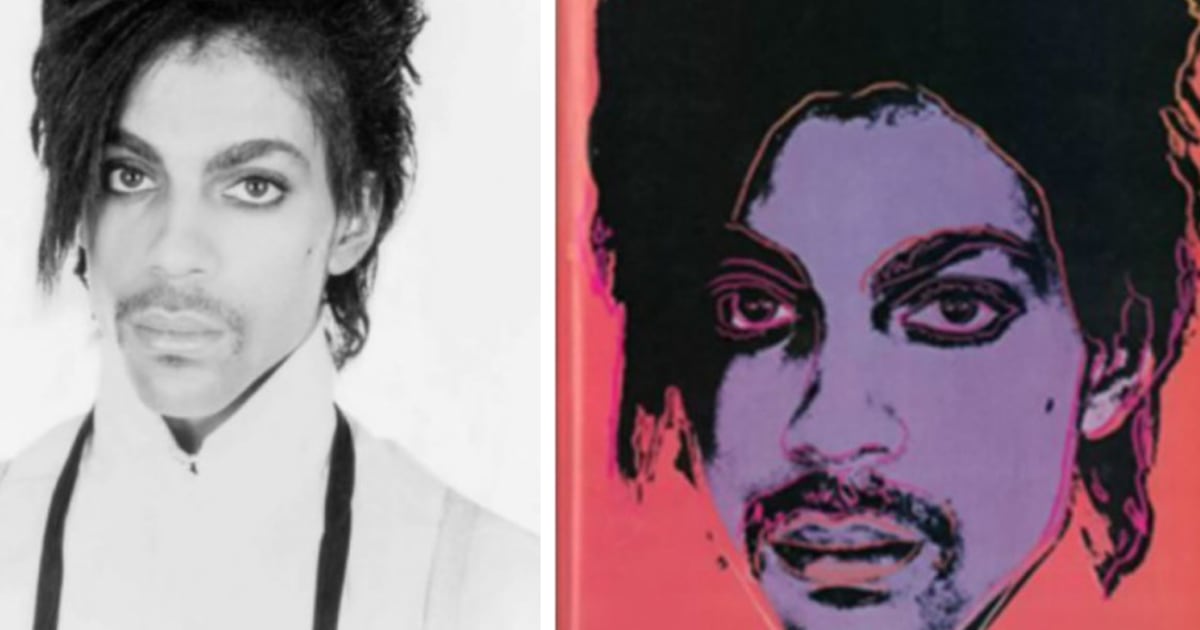

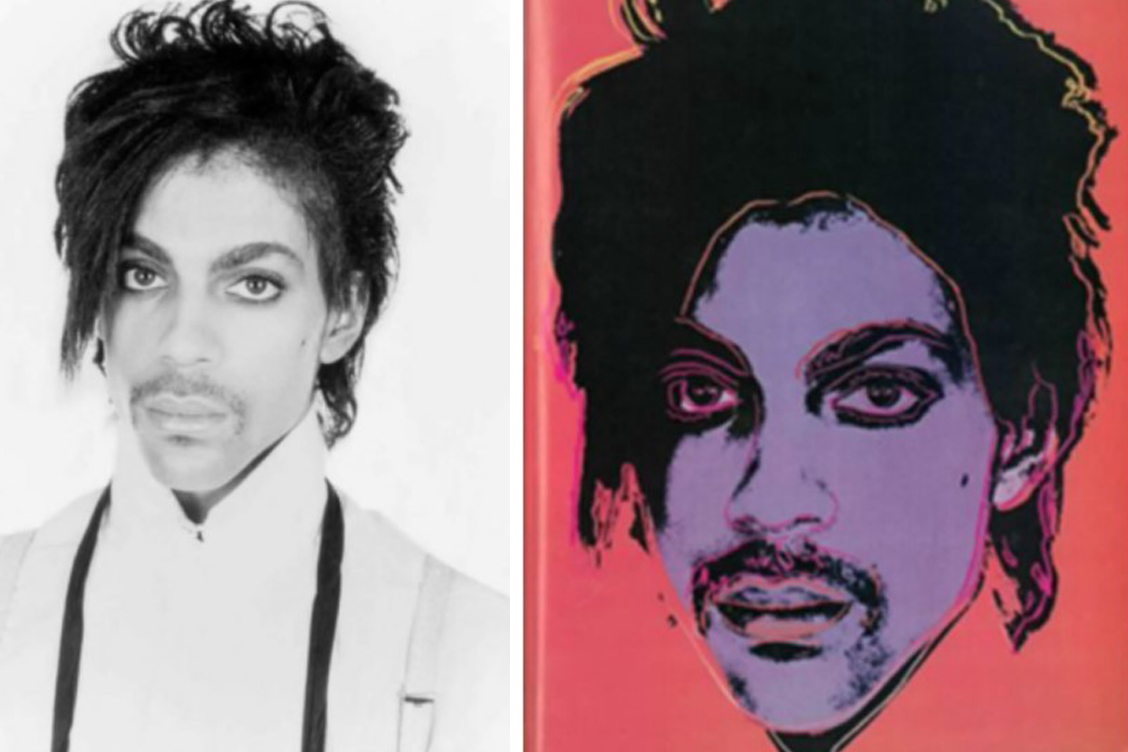

Goldsmith sued over Warhol’s use of her 1981 photograph of Prince, then a rising star, before he attained global fame on the back of hits like “Little Red Corvette” and “When Doves Cry.” As part of an arrangement with Vanity Fair magazine three years later, Warhol created a series of silkscreen prints, as well as two pencil sketches, based on Goldsmith’s image. While the original photo, a portrait of Prince, was black and white, the silkscreen prints superimposed bright colors over a cropped version of the original photo. The style was similar to that of other famous Warhol works, such as his portraits of Marilyn Monroe.

Under a license it had obtained from Goldsmith, Vanity Fair used a Warhol illustration based on the photo in its November 1984 issue without any problems arising. But Goldsmith said she was not aware that Warhol had created other images that were not licensed, a fact she became aware of only after Vanity Fair publisher Condé Nast used a different image as part of a 2016 Prince tribute immediately after his death.

Warhol died in 1987, and the relevant works and copyright are held by the Andy Warhol Foundation, which permitted Vanity Fair to use the image in 2016. Goldsmith was not credited.

The next year, the issue ended up in court, with Goldsmith and the foundation suing each other to determine whether Warhol’s image constituted fair use.

In 2019, a federal judge ruled in the foundation’s favor, saying Warhol’s images were transformative because, while Goldsmith’s photo showed a “vulnerable human being,” the Warhol prints depicted an “iconic, larger-than-life figure.”

The foundation sought Supreme Court review after the New York-based 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Goldsmith in March 2021. The appeals court faulted the district court for focusing on the artist’s intent, saying a judge “should not assume the role of art critic.” Instead, a judge must examine whether the new work is of a completely different character from that of the original, the court said. It must, “at a bare minimum, comprise something more than the imposition of another artist’s style on the primary work,” the court added.

As part of the case, the justices debated a relevant Supreme Court precedent cited by both sides, a 1994 ruling in which the court held that it was fair use when 2 Live Crew created a song called “Pretty Woman” that was a parody of Roy Orbison’s “Oh, Pretty Woman.”

Various interested parties filed briefs advising the justices about what approach to take, including movie and music industry groups, educational institutions and individual artists. Universal Pictures, a division of NBC News’ parent company, NBCUniversal, is a member of the Motion Picture Association, which filed a brief in support of neither party.